Meet Roger W. Smith – Watchmaker extraordinaire !

He can spend a week producing a tiny cog that his rivals might churn out in a few seconds. Just one sneeze can make a month’s work disappear into thin air (it happened once).

He can spend a week producing a tiny cog that his rivals might churn out in a few seconds. Just one sneeze can make a month’s work disappear into thin air (it happened once).

Everything about his production line is studiously low-key — the building, the people, even the name for that matter.

You could drive past this remote corner of the Isle of Man every day for 20 years without ever realising it is a factory — let alone that it is the headquarters of a world leader in his field who also happens to be Britain’s latest trade ambassador.

At present, there are only 50 people on the planet who own a Roger W. Smith watch. And they are always going to be a pretty exclusive club. For although Roger has received many accolades, he is seldom described as ‘prolific’.

He currently manufactures ten watches each year — ranging from £85,000 to £500,000 each — although Roger has plans to crank up production to, wait for it… 12.

But that is exactly how he likes it. Indeed, he has a corporate mantra that would be anathema to any other boss: ‘No one makes fewer!’

One of the latest pieces to come crawling off the production line is a watch worth £180,000 — and Roger hasn’t received a penny for it. Commissioned by Downing Street as part of its ‘GREAT Britain’ overseas trade and tourism campaign, it will be unveiled in London next month.

It will then accompany ministers and diplomats on trade missions overseas, in a special display case made by Viscount Linley, as an exemplar of British style and ingenuity. Because no one else on Earth produces watches quite like Roger Smith.

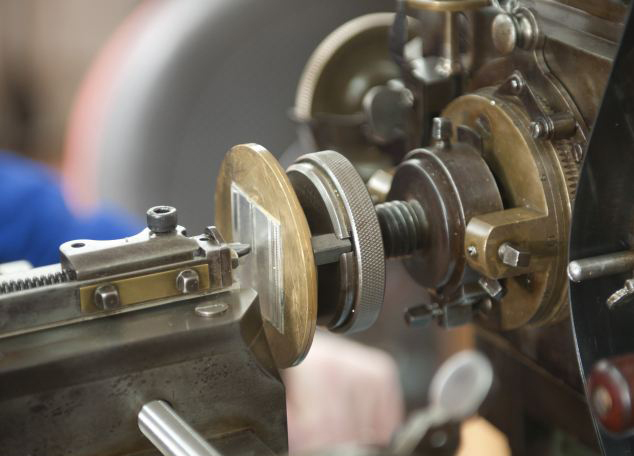

The title of ‘watchmaker’ is granted to anyone who can mend or assemble a watch. Bolton-born Roger, 43, is one of a tiny handful of people with the requisite abilities to make the whole thing. Of the 34 different skills required to create a mechanical watch, he performs 32 of them himself. Even the most exalted Swiss watchmakers can’t do that. They will have a variety of people making all their components and others assembling them. Roger and his tiny team of five hand-make every screw, dial and cog on their own machines, two of which date back to 1820.

They then piece them together themselves. The only parts they source elsewhere are two springs and the leather strap. That is why collectors all over the world are prepared to pay up to £500,000 for a timepiece engraved with ‘RW Smith’ on the face (his middle name is William). But they had better strap something else to their wrist in the meantime. Because the waiting list can be as long as eight years. These are watches that need winding up every couple of days. But they are as close to the essence of watch-making as any watch can be. For Roger is the anointed successor to the man regarded as the greatest watchmaker of modern times.

Not bad for a chap who was once a repairman for Ratners….

Roger’s career is a morality tale for modern youth. There is a touch of Aesop or Hans Christian Andersen about the boy who did not excel at school (though his careers adviser thought he might make a competent quantity surveyor). But Roger loved making things.

When his father, a doctor, enrolled him on a Manchester watchmaking course, he realised he had found his calling. One day, Dr George Daniels came to deliver a guest lecture.

In horological (timekeeping) circles, the late Dr Daniels commands parity with the greatest of engineers and designers. He was the man who overcame the centuries-old problem of friction with an invention called ‘co-axial escapement’ — hailed as the most important horological development in 250 years.

Roger was so impressed by the lecture that he decided, there and then, to make his own watch. Nearly two years later, he took the result to Daniels’s home on the Isle of Man. The great man was well-known for his forthright views. He took one look at Roger’s work and declared: ‘Too handmade. Try again.’ At which point, most people might have called it a day. But Roger went back to Manchester where, by now, he had secured a full-time job servicing Tag Heuer watches. He threw it in, took part-time work doing repairs for Ratners and spent the rest of his time at home building a second watch from scratch. His only guide was a copy of Dr Daniels’s industry bible, Watchmaking.

It was five years before Roger felt confident enough to show his next attempt to the time lord. ‘I’ve never been so nervous. I walked up the drive, thinking: “It’s taken me seven years to get this far. What if it’s no good?” I showed George my watch. He looked at every part. “Who made this?” I said: “I did”. “Who made that?” “I did.” Finally, he said: “Congratulations. You’re a watchmaker.” That was it.’ Daniels went on to give Roger the ultimate accolade — an apprenticeship. He moved to the Isle of Man and worked in his mentor’s workshop for three life-changing years before setting up on his own in 2001.

When Daniels died in 2011, aged 85, his fortune — including a £10 million vintage car collection — was split between his ex-wife, his daughter and a substantial educational trust in his memory. But he left the contents of his workshop to Roger to carry on the traditions.

Roger’s old cottage is now his factory (he lives elsewhere with wife Caroline and their baby daughter). In one room, ancient hand-powered lathes sit alongside the latest in computerised equipment. Head through the kitchen and another room houses the desks where the hand-made components are painstakingly pieced together.

It’s a happy atmosphere. The longest-serving member of the team, Andy Jones, 48, was at college with Roger. Nicholas Wolfe, 34, and Scott Weaver, 28, were both working for big Swiss watchmakers but jumped at the chance to work with the heir to George Daniels.

Roger has recently taken on an apprentice, too. Josh Horton, 24, is patiently sinking 85 microscopic teeth into a single cog. It might take all day. A big Swiss brand will stamp out the same part in a couple of seconds. ‘Our clients like to know that there’s this sort of craftsmanship in their watch,’ says Roger. ‘And we don’t use new materials.’ His basic ingredients are gold, silver, platinum, steel and nickel.

Sitting on Roger’s desk at present are the half-finished innards of a ‘very complicated’ commission, which will cost ‘about £500,000’. He opens a drawer and produces his latest result, a £180,000 specimen destined for a buyer in Hong Kong.

It’s all wrapped in protective film. It’s a decent weight but not remotely clunky. Roger points out some of the intricate details such as the ‘English finish’, the frosted metal, even the unique sculpted design of the tips of the hands. The back is transparent so you can see the exquisite workings and a tiny silver triskelion, the three-legged emblem of the Isle of Man.

What sort of a person buys a watch like this? Roger has made just over 60 so far, with buyers spread from the U.S. to China. A few collectors own more than one. And their priority is not split- second accuracy.

‘If you want the precise time, then a quartz watch will do that,’ he says, pointing out that a good battery-powered watch might have a margin of error of three seconds a month whereas a very good mechanical one might lose or gain five seconds a day.

But that’s not the point. ‘I love something that’s alive, that has a pulse, that is going to carry on working beautifully for 200 years,’ he explains.

Intriguingly, he says that most of his clients tend to produce things rather than just shuffle money around. ‘I suppose people who create or manufacture understand the challenges of making something like this,’ says Roger.

These watches have none of the bling or brand status that might appeal to a footballer or a City bonus boy or the target audience for those hilariously smug Patek Philippe ads (with the banker Dad, the spoilt son and the cheesy slogan: ‘You never actually own a Patek Philippe; you merely look after it for the next generation’).

With a two-year waiting list for the most basic £85,000 Roger W. Smith model, no one is ever going to buy one on impulse. Are they waterproof? ‘Yes, down to 160ft. But I don’t encourage it. It’s not good for the strap!’

While Roger admires many of the big Swiss names, he points out that most of the great breakthroughs in timekeeping have been thanks to Britons — from John Harrison, whose sea clock solved the riddle of longitude, to Thomas Mudge, watchmaker to George III who invented the lever escapement (found in most watches to this day), not to mention George Daniels. After all, the whole world sets its watch against Greenwich Mean Time.

‘From the 1600s to the 1800s, we were the masters,’ says Roger. ‘Then it was the Americans and then the Swiss. But we’re still here.’

That’s why he is delighted that the Government will soon be using his work to promote the best of British around the world.

But he still has one major challenge.

Has he managed to sell one of his watches to Switzerland? ‘No,’ he says, adding quickly: ‘Not yet.’

.